Living With Intention in a World of Excess

- Minimalism, rooted in ancient philosophy, is about stripping away excess to focus on meaning and purpose.

- Historical figures like Diogenes, Buddha, and Thoreau lived intentionally by rejecting material distractions.

- The modern minimalist movement emerged as a response to consumerism, valuing simplicity and function over clutter.

- Today, minimalism appeals to a generation overwhelmed by digital excess, financial struggles, and environmental concerns.

- True minimalism isn’t about deprivation but about curating life for clarity, focus, and meaningful experiences.

From endless unread notifications, to mountains of laundry with missing sock pairs, and even the rotten groceries in the back of the fridge that never get eaten. How is decadent clutter creating dysfunction in your life? At what point is abundance too much? When it starts to impede your ability to focus on your priorities that you've written out for yourself. To truly be an agent of your own will you'll want to remove the obstacles in the vision of your dreams. Decadence is the enemy of dreamers and independent thinkers. Without mindfulness in our consumerism we can easily become digital gluttons, slowed down by the weight of our attention spans overflowing to every stimulus except our highest goals. Let's discuss where minimalism came from, and how it resolves that dysfunction.

I.

Before minimalism was cool, or a word really, there were some thought leaders ahead of their time championing its benefits.

Diogenes of Sinope was the most prolific Cynic in human history. And a kind of punk rock bastard if I'm honest. The man didn't give a fuck. When the most powerful man on the planet asked him to make any earthly wish, and it'd be done for him, Diogenes told Alexander the Great, "Yes, that you should stand a little out of my sun."

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

Not a soul exceeded Diogenes in self-sufficiency. At one point he owned nothing more than the clothes on his back and bowl to eat and drink from. But when he saw a child drinking water with his hands, the philosopher was not to be outdone. So he trashed his bowl in favor of eating and drinking with his own hands. The intellectual saw earthly possessions as distractions from the highest call of humanity: to live in accordance with nature. For him, minimalism wasn't merely stripping material possessions, but even his own emotions, when considering life's purpose.

The middle path of Buddhism is consistent with the message of Diogenes. That suffering comes not from having less, but desiring more. What they have in common is that abundant wealth comes from within. To them maybe missing out on consumerism isn't as big a deal as spiritual poverty. In the Buddhist context wanting more resembles an underappreciation of what you already have. And before we even talk about what you have materially we have to talk about being in possession of yourself. And if you're ungrateful for being in possession of yourself then you must be suffering a truly expensive poverty. Through detachment, Buddhism invites us to material disillusionment, and to enjoy the most important parts of our lives, ourselves, the rich relationships we enjoy with each other, and nature.

Transcendentalist philosopher, Henry David Thoreau, published Walden; or, Life in the Woods in 1854 to describe the two years, two months, and two days he spent living in the wilderness alone. The man was on a mission to make a statement about the "over-civilization" of society by living a simple life connected to nature. Of course he wasn't naive about the prospect. Good or bad, the American Romantic period inspired Thoreau with transcendentalist philosophy that had him believing that spiritual phenomena are a part of real dynamic processes rather than mere ideas. And if that were the case, then it should be evident when living in nature. Whether that spirit was nice or mean wasn't something Thoreau was there to judge.

"I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion." --Grammardog Guide to Walden, by Henry David Thoreau

More popular among netizens is stoicism. A philosophy associated with cool level-headedness in the face of adversity. Being realists, they never assumed material wealth was inherently good or bad. They just viewed too much of it as clutter. One of the big goals of stoicism was to control one's reactions to external events. The kind of clarity required for such a temperament called for mindfulness in every facet of the stoic's life. Mindfulness of material possessions and commitments helped prune the still garden in the mind. If your room is supposed to be a reflection of the mind then stoics managed their homes with the same caution as their thoughts. When you have too many possessions your thoughts get stretched thin. You might think to react to the stove that's still on, a computer that's overheating, a game that's not paused, a smart watch you still haven't charged, all the while you still don't know if you gathered all the pieces of your favorite board game or if a piece fell under the sofa. How can you control your reactions to the world if you're over-complicating your own private life before you even deal with the external?

“It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor.” --Seneca

For the historical greats that preceded the minimalist art movement, minimizing material possessions was about stripping away parts of our lives until we can reduce it to what's most important. Giving them much needed focus and clarity, ancient philosophers made history by keeping their eye on living intentionally and meaningfully. They showed us that before minimalism was a fully realized art movement, it was a lifestyle. One that protects devotion to meaning and purpose.

II.

By the 20th century, minimalism would evolve as a reaction to post-WWII consumerism, and its subsequent Abstract Expressionism. Neither of which seem odd to me. Whenever I see someone victim to their own overconsumption I assume I'm dealing with someone who's suffered scarcity whether that was through financial poverty or the neglectful/abusive rule of someone they had to work or live with. So it makes sense that a nation plagued by one of the greatest tragedies in human history would immediately chase that trauma with decadence. Every unnecessary splash and splatter on a Pollock painting speaks to me of a compensation for something else lacking. And US consumerism was swinging out of a period where manufacturing was mostly focused on supporting the military industrial complex out of necessity. The privilege to make something that wasn't for the exclusive purpose of war had arrived. I don't blame them.

But with time history became legend. And the generation that remembered that era was aging out of popular culture as a newer younger generation assumed cultural dominance. They had no social context for the trauma that led to abstract expressionism or postwar consumerism, and didn't think it was that pretty to begin with. An aesthetic key of a bygone era of has beens. Minimalism reacted to abstract expressionism with clean lines, geometric shapes, and repetition.

Minimalist American artist, Donald Judd, focused on pure form rather than personal expression using industrial materials. He was a real no bullshit artist, and father to the minimalist wave. By stripping away the bells and whistles of his craft, Judd sought visionary autonomy and clarity. Not just for the object crafted, but the space that object subsequently dictates for the space of the room. After the fresh hell of disposable manufactured goods that came with postwar industrialism, Judd wanted to reduce his space to a functional design.

Agnes Martin was from Canada, but would settle into New Mexico where she'd have a historical influence on artistic minimalism. She was a profoundly introspective figure, and that reflected in her art. Much of it involved the fewest number of colors possible along repetitive geometric patterns. Not much to look at. But therein lies the art. Personally, when I compose a canvas, before I consider a single detail, I consider how the shape, form, and generalized values will move the eye around the canvas. That dynamic movement of the eye creates energy in the canvas giving my work life. Agnes would have none of that. Although her work might resemble something closer to bland wallpaper than a dynamic expressive painting, that was the point rather than a fault. Through her minimalist approach to her work, it's almost as though she invites the audience to be still. Stop shifting those eyes around looking for the point and meaning behind art. Perhaps by being still she invites viewers to gaze inward. To use that creative energy on spiritual progress rather than vain expressions of individualism.

Dan Flavin might be the reason we have TikTok aesthetics the way they are now. Every talking head seems to have LEDs plugged into the back of their furniture these days. His creative path began with sculpting, but his contribution to minimalist art would be his fluorescent lighting. He demonstrated a high level appreciation for contour, color and shape through his use of neon lighting. Most of his work was untitled, but dedicated to people who mattered to him. His work doesn't say too much, but what it does say speaks to the very walls of room, and the space between them. Minimalism didn't seek so much to draw attention to itself, but serve the space it occupies. But for all its functionality the visual aspect tries not to take away from the room as much as it tries not to add too much either.

Wabi-sabi was basically the Japanese contribution on minimalism. It's both austere and rustic leaning into its English translation. The Japanese aesthetic is born around acceptance, transience, and imperfection. It hails from the Buddhist principles of impermanence, suffering, and emptiness. Wabi-sabi's aesthetic is designed around principles of asymmetry, roughness, simplicity, economy, austerity, modesty, intimacy, and the appreciation of both natural objects and the forces of nature. It seeks to fuse a harmony between artificial and organic forms. A calming minimization that doesn't merely reduce artificial shapes, but puts it back in the context of nature. Something even Diogenes could enjoy.

Today, the legacy of minimalism continues to pervade through western society. Brands like Apple embraced the less-is-more philosophy reducing digital clutter giving meaningful focus to their products that lends their catalog to minimalist principles. Streamlined design echoes through their software and hardware. Brands like Muji and IKEA seek to reduce clothing and furniture to their most functional design. Although it may not feel reduced to the first time dad trying to figure out why he has spare parts after finishing assembling a chair.

The minimalist art movement proper isn't directly related to the philosophical minimalism of antiquity, but they have common principles like sustainability and mental clarity. Diogenes renounced material possessions to live harmoniously with nature. Wabi-sabi sought to do the same, albeit to less of an extreme. And Judd's divorce from decorative clutter inspires a modern rejection of fast fashion and digital noise.

III.

So why is minimalism still gaining traction today? We haven't maintained the circles around abstract expressionism the same way. What makes minimalism different? Maybe it's because today's generation has more in common with artists and critics from the 50s and 60s than they do with the postwar generation.

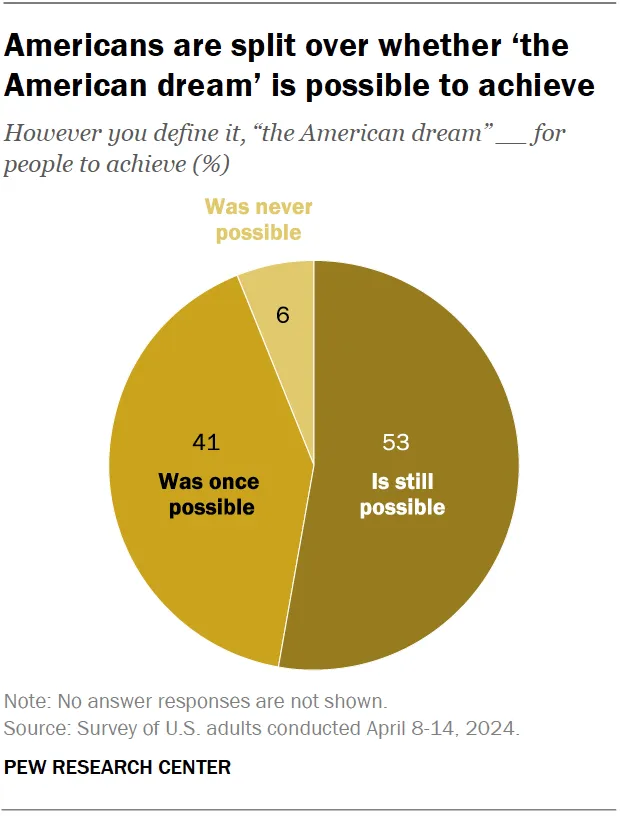

A steep decline in public belief in the so-called "American Dream" has a lot to do with it. A study by the Pew Research Center shows that 41% of Americans believe it might've been possible in the past, while 6% believe it was never possible at all. Collective discouragement in the dreams sold to postwar boomers has made us tired of the bullshit. We're more straight-shooters than the generations that preceded us. Disillusioned with the cave shadows that have been peddled to us, modern society just wants to know what's real about our current socio-economic climate, and how we can fix it. We're not the homey cluttered group that America used to be. Partly because we financially can't afford clutter without becoming devoted hoarders.

The Information Age exacerbates that unrest with digital overload. We're fed an endless Sisyphean stream of doomer notifications that have us questioning our grip on reality, and whether we as individuals even have any context in the direction the world is moving. Vapid influencers, non-stop notifications, labyrinths of app storage, and losing track of streaming subscriptions so badly we need more apps just to help us track them have all contributed to the society's silicon fatigue. We're hungry for less. Today's economically disadvantaged Americans hold digital decadence in one hand, while holding empty wallets in the other. They want less bullshit, and the ability to focus on the path of least resistance to a more sustainable future for themselves and their families.

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

At the same time we're collectively becoming more environmentally conscious. Climate change is becoming undeniable with record-breaking summers, rolling blackouts, undrinkable water, stunted supply chains, and unhinged presidential trade wars have everyone questioning what's really possible with US materialism. The state of Texas is forecasting a need to build the equivalent of 30 nuclear reactors just to keep up with the demand of electricity to support the expansion of AI and crypto mining over the next decade. The lone star state wants to become the data hub of the country, and possibly the world. An ambitious dream for a state that just 2021 subjected its residents to rolling blackouts because it didn't have enough power through the ERCOT power grid to keep homes heated during what the locals called "snowmageddon." Yet all of this development is supposed to be possible after Trump hikes 25% tariffs on our allies who support us with the materials we'll need to build that data-focused infrastructure.

A lot of this comes down to a collective desire for mental health and peace of mind. For all the conveniences of the modern Information Age it's come at the expense of our serenity. The human brain hasn't structurally evolved in tens of thousands of years, if not more. And the same organic gear used to spend all day hunter-gathering is supposed to be used to keep us up with all this over-stimulation. Something's gotta give. As an overburdened society we're beginning to realize that we just can't do it all. We can't be aware of everything, or care about everything. Political engagement has to be minimized to just what individuals care about the most. Their daily lives need to peel off the dopamine addictive feeds that glue them to their phones. There's just not enough time for all that. Burning our artificial world has reinvigorated an appreciation for nature, simplicity, and authenticity. Principles that line up perfectly for minimalism.

IV.

Minimalism is more than a vanity aesthetic. It can't be reduced to just owning a set number of things, or even having less for its own sake. It's about doing more with less. It's about living with intention. That intention comes from not just owning less material possessions, but asking ourselves the important questions. Like, why do I own this? What role does this play in my life? Do I really need another social media app, branded shoes, or the missing furniture item that completes my set? Or does everything in my space serve a function oriented to my highest purpose that I've written for myself?

The aesthetic serves as a reminder of what we're living for by removing what we don't need for that life. It's for people who are tired of being digital victims to technocratic elites who prey upon our attention spans with endless algorithmic consumption. And it's for the those who find it impossible to focus on their passion in a cluttered home environment. More than vanity, minimalism is a function of mindfulness. Which is why even ancient philosophers had principles that foreshadowed the art movement. It's almost like focus through decluttering is a natural conclusion to anyone with a sense of purpose in life.

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

More and more, folks crave experiences over possessions. Plenty of my friends will forgo large purchases so they can afford airplane tickets and lodging reservations. People want to feel something for once in their lives. In a world as discouraging as the dystopian one we live in, I don't blame them. We have a finite amount of money, and more folks are realizing that money can either go to cluttering their homes with objects they will end up walking by day by day as they desensitize themselves to their own home environment, or go fight a Thai fighter in Thailand. Or whatever people do when they travel for fun. Traveling martial artistry sounds exciting to me.

Removing clutter for its own sake isn't the point. It's to remove obstacles to the vision of our meaning for being here. The German-American painter, Hans Hofmann, once put it into perspective with words like:

"The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.”

But when the purpose behind minimalism is bastardized from it, then we have something vapid and meaningless. Which is the "counter-argument" to minimalism. I put counter-argument in quotations because removing the utility of minimalism is really a straw man caricature of what it really stands for.

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

When essential items come down to Patagonia jackets and Coach bags, while TikTok influencers reduce minimalism to a consumable aesthetic for an addictive algorithm--the art movement starts to look more like a privilege in disguise. These shallow representations of minimalism are more something Plato would liken to a shadow on a cave wall than a real representation of the principles it's supposed to stand for. We're not doing this for deprivation itself, like some kind of masturbatory self-referential virtue-signaling. More than depriving materialism, minimalism seeks to proliferate intentionality and mindfulness. It's just like the author of The Art of Owning Less, Joshua Becker, used to say:

“Minimalism is not about having less. It’s about making room for more of what matters.”

V.

When the aesthetic stays connected to the principle, the benefits of the virtue become more accessible. Decluttering becomes curation. Insead of getting rid of things for the sake of getting rid of them, we start to ask ourselves, what items in our home mean the most to us? What items give me a story to tell visitors? What items facilitate my daily work and chores? What items inspire me to keep pushing in a demotivating world?

Capsule wardrobes keep us mindful to the versatility of the clothes we buy, and give us a little more commitment to the signals of our expression with a limited wardrobe. Does this shirt really tell everyone at the bar that I came here to be alone? Well maybe that's a musing for introverts. But maybe the opposite is true for extroverts. What blouse will get me the most free drinks at the bar? Or whatever extroverts think about.

Financial minimalism shouldn't be about cutting costs for the sake of depriving your lifestyle. It should make you more mindful and appreciative of the meaning behind the money you spend. Are all of those costs in your life necessary? Are they doing something meaningful for you, your work, or your family? Does your bonsai tree really need that new pair of slippers? Or could that money be better spent on getting your plant a more dignified pot? Should your money be paying for a blue checkmark on Twitter feeding the technocratic agenda of an oligarch wannabe? Or could that money better serve the public good by donating to decentralized democratic platforms like Mastodon?

Time minimalism is a slippery one. Our time can go in a variety of directions really fast without any meaning or purpose behind them. Especially when social media algorithms monetize your attention captivity for the benefit of advertisers. You could spend that screen time learning a new skill, or getting informed on global issues that actually matter to you. Netflix binges seem innocuous. But are you consuming for entertainment's sake itself, or are you watching documentaries and biopics that contextualize your craft, personal life, and worldview? You get a finite amount of seconds to breathe on this planet, and you should want to make them count. You're not getting any of those minutes back. Your time should be spent on you, rather than the advertisers that profit from your algorithmically manipulated attention span. Take your power back by orienting the sands in your life's hourglass to your highest priorities.

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

Derek GuzmanDerek Guzman

What would your life look like if you trim the fat and cut away the excess? Who are you when everything is taken away? What do you stand for when materialism is cut out from under you? What's left when you remove everything from your life that doesn't serve you?

Those are the kinds of questions we should be asking when adopting minimalism more than any vainglory. Even virtue for virtue's sake is not a virtue. Temper minimalism with thoughtfulness. It's not about taking things away from you. It's about charging meaning and purpose into what you do have, and remove the obstacles to a clear mind that paves the way for the pursuit of happiness.